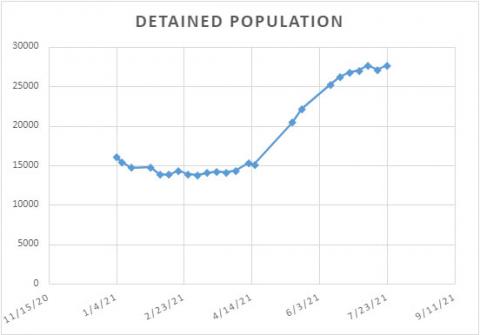

Despite the Biden administration’s substantial commitments to reduce the use of immigrant detention and address punishing conditions for people held by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), its track record since inauguration has gone in the opposition direction. The ICE detention population has increased by more than 80%, including a sharp increase in the detention of asylum seekers. The Biden administration must take bold action quickly to reduce its reliance on immigration detention, and the legal mechanisms exist that make it possible.

Data source: https://www.ice.gov/coronavirus#detStat

President Biden promised as a candidate to end privatized immigration detention and after inauguration announced his administration will phase out the use of private prisons in the criminal system. Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas has testified to Congress that he is concerned about the “overuse of detention” and, in announcing the closure of two ICE detention facilities in March stated that, “we will not tolerate the mistreatment of individuals in civil immigration detention or substandard conditions of detention.” But slow-moving reform or a slow trickle of facility closures is not enough for those trapped in the United States’ abusive and often deadly immigration detention system.

This white paper outlines key steps the administration can take immediately to I) cut the contracts for a significant number of detention facilities and II) promulgate new rules to end privatized immigration detention and the unjust, wasteful presumption that immigrants should be detained without basic due process protections during their civil legal proceedings. All of these goals are within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)’s legal authority and discretion.

I. Cut the Contracts

The administration must immediately place a freeze on new contracts currently being negotiated and use its broad authority under federal law to begin terminating existing contracts with private prisons and local governments. When a facility is closed, the administration must ensure that those detained in that facility are released to the community or to community-based alternatives-to detention-programming, not transferred to other detention centers.

The United States’ immigration detention system is a vast web of dozens of private prisons and county and local jails that contract with ICE. Neither the contracts nor the inspections regime governing these facilities is uniform, creating opacity and impunity. But although the web of ICE detention contracts is complex, the government never has its hands completely tied. Specific provisions in each type of detention contract, combined with principles of government contract law, allow DHS to terminate contracts and significantly reduce ICE’s detention infrastructure without delay.

A. Use contract provisions allowing for early termination or contract expiration.

ICE’s most used detention contract vehicle is known as the Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSA), involving a contract between ICE and a state or local governmental entity (e.g., a county sheriff, town, or city government). IGSAs are used to hold people in detention facilities exclusively utilized by ICE known as “dedicated IGSAs” or to rent out bed space in county jails or similar facilities that also hold people charged with crimes, known as “non-dedicated IGSAs.”

Dedicated IGSAs usually include a “pass-through” arrangement involving private prison companies, which allow local governments to act as middlemen and ICE to side-step procurement laws that govern contracts with private companies. The counties or municipalities hosting the detention centers then receive kick-back funds from the private companies. For example, under its dedicated IGSA, the Town of Farmville, Virginia, collects around $240,000 a year to act as the intermediary between ICE and the company Immigration Centers of America (ICA), which takes in around $24 million a year to operate the ICA-Farmville detention center.

Terminating dedicated and non-dedicated IGSAs is simple. IGSAs include a provision that allows DHS to end a contract simply by providing written notice to the local government, typically 60 or 120 days in advance. After termination, ICE then issues a “task order modification” which confirms close-out of the contract and de-obligates any remaining funds. This process is nearly identical whether an IGSA is dedicated or non-dedicated.

ICE also contracts directly with private prison companies. These contracts are among the simplest for the administration to exit. The majority of direct contracts between ICE and private prison companies last for one year, referred to as the “base period,” with a series of one-year “option years.” The government has no obligation to exercise option years, and can simply decline to exercise the next option year, which terminates the contract. In other words, by deciding not to go beyond the current year of contract, the government can end its contract with a private company without required written notice.

Finally, ICE sometimes enters into agreements with the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) to join an existing USMS detention contract or agreement to use USMS-acquired bed space in a local prison, jail, or private detention facility. This is known as a “rider” on a USMS contract. These riders also include provisions allowing for written notice of termination before the end of a set contract period. In other words, the administration can and should terminate USMS riders simply by issuing written notices of termination

B. Terminate detention contracts on the basis of “government convenience” in absence of other options.

Even absent an explicit termination provision or the annual option to opt-out, the administration always maintains full authority to end contracts with private prison companies and local governments under principles of government contracting law. The government generally maintains the right to end any contract for services prior to its expiration when it is in the government’s interest to do so, a principle known as the “termination for convenience” doctrine.

The “government’s interest” is broadly defined in this context. A policy decision by the Biden administration to end the use of privatized immigration detention, for example, should be considered within the scope of the government’s interest. The government can rely on this doctrine to end a contract, regardless of the structure of the contract, and even if the contract guarantees payment for a certain number of “beds” (often referred to as “guaranteed bed minimums”).

II. Promulgate New Rules

The administration should also issue new regulations and revise existing ones to fulfill its promise to decrease immigration detention.

Over the past few decades, ICE has significantly contracted out its detention authority to private prison companies — despite having no statutory authorization to do so. Further, the current regulatory framework prioritizes detention over liberty, at the expense of human rights and constitutional norms. The administration should issue new regulations that 1) end privatization of the detention system, 2) re-orient the immigration system toward the assumption that people should live in freedom while pursuing their immigration cases, with detention as the exception, not the norm, and 3) end unconstitutionally prolonged detention.

A. Issue regulations that end privatized immigration detention.

For decades, DHS has largely outsourced its detention system. About 67% of ICE detention facilities are owned or operated by private prison companies such as GEO Group, CoreCivic, LaSalle Corrections, and Immigration Centers of America (ICA).

But DHS has engaged in this practice without statutory authority. In current litigation over the legality of California Law A.B. 32, which bans most private detention in that state, the government and GEO Group, Inc. have been unable to point to any provision in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) or elsewhere that authorizes DHS to contract out its detention authority to private prison companies. The provision that the government has pointed to for justification, Section 241(g) of the INA, only permits DHS the discretion to purchase or rent physical places for detention, it does not authorize DHS to contract out the agency’s detention authority.

That silence in the statutory scheme presents an opportunity for the administration to permanently end DHS’s reliance on private immigration detention through new rulemaking. It can do so by promulgating regulations relating to Section 241 of the INA, and specifying that DHS is not authorized to contract or subcontract out its detention authority to private prison companies, with a one-year required phase out period.

B. Issue regulations that presume liberty rather than detention for those undergoing civil immigration proceedings.

The INA gives the executive branch wide discretion in enforcing civil immigration laws, including whether or not to detain a significant percentage of people facing immigration proceedings. Yet, the current federal regulations impose a default of detention for all people in immigration proceedings, an approach not required by the statute. ICE officers and immigration judges begin proceedings with the assumption that the people before them should be detained, placing the burden on the immigrant to prove otherwise. This approach to immigration detention has resulted in the vast jailing of asylum seekers and community members, often for prolonged periods of time, and without any meaningful individualized consideration of release. Numerous federal courts have held that placing the burden on the immigrant in custody hearings violates due process. And yet the practice persists, without statutory mandate.

The administration should issue new regulations that redirect discretion toward a presumption of freedom rather than a presumption of detention. Immigration adjudicators should be required to start proceedings with the assumption that people should be free to live in their communities while their immigration cases are pending, either released on recognizance or with community-supported programming as needed.

DHS should begin the process of rulemaking to revise 8 C.F.R. § 236.1(c)(8) and promulgate new regulations to codify the agency’s discretion to release individuals during their court proceedings, limit the circumstances in which the agency will utilize its discretion to detain, and place the burden on the government to justify detention.

In its revised rules, the administration should ensure that DHS is required to justify a decision to detain, in writing, by clear and convincing evidence. The current practice of checking a box on a custody-determination form is insufficient. Furthermore, the agency should not be permitted to rely on unreliable evidence such as police reports to meet this burden, and should be required to evaluate past criminal convictions in the context of all relevant evidence, including the recency of such convictions, efforts at rehabilitation, employment history, and ties to the community. Furthermore, regulations should ensure that no one is detained simply because of an inability to pay a monetary bond, and that the use of onerous and harmful conditions of release such as ankle monitors is prohibited or strongly disfavored.

C. Issue regulations that end prolonged detention.

People in ICE custody have few mechanisms of redress to challenge prolonged detention. Those who are given a preliminary review can only seek reconsideration by demonstrating that “circumstances have changed materially since the prior bond redetermination.” Even worse, many people are detained by ICE under restrictive provisions of federal law (sections 236(c), 241(a) and 235(b) of the INA) that are interpreted by the agency to preclude any access to immigration court review even when their detention has become unconstitutionally prolonged.

The result is that people are often detained by ICE for months, even years, without any mechanism for the immigration court to review the fairness or constitutionality of their continued detention. Many endure this prolonged detention without ever accessing a bond hearing before a judge; others receive a preliminary review of their detention but have no way to raise the constitutional issues that arise as their detention becomes increasingly prolonged.

No other area of U.S. law allows for prolonged, indefinite detention without an individual determination on whether detention is necessary. In the criminal legal system, no matter the seriousness of the charge, people who are arrested are entitled to individualized bond hearings where the burden is on the government to demonstrate whether pretrial detention is necessary. Such detention is typically subject to continuing review by a judge with the power to modify the initial determination. If a person is then convicted of a criminal offense, they are sentenced to a definite period of time with a set end date. Yet in the immigration system, there is no mechanism for judicial review of prolonged detention, despite indefinite periods of detention lasting months or years. And there is no set end date to immigration detention - the agency retains and routinely exercises its authority to detain until all immigration proceedings, including appeals, have concluded, even if an immigration judge grants relief at the trial level. At NIJC, we see the stress this indefinite, prolonged detention imposes on our clients, many of whom have been detained for years without ever having had the opportunity to ask a judge to consider whether their detention is justified or necessary.

The Supreme Court has upheld ongoing immigration detention as a statutory matter in a case called Jennings v. Rodriguez, but the Court explicitly left open the possibility that prolonged detention might violate the Constitution. Since Jennings, numerous federal courts have held that unreasonably prolonged detention without a bond hearing violates the Fifth Amendment right to due process.

New regulations must redress this unconstitutional injustice. ICE should initiate a rulemaking process to revise 8 C.F.R. § 1003.19(e) to expand access to judicial review of detention and create a regulatory scheme that would enable immigration judges to consider and provide redress for the due process problems posed by prolonged detention.

III. Reverse Course: Detention is Not the Answer

This June, NIJC client Maura spoke to The Guardian about her experience of trauma and loss in ICE detention. She explained that she was “initially hopeful that things could change under Biden when she heard news about the executive orders he was targeting in his first 100 days,” but at the time of the interview felt that “those of us still detained have been forgotten.”

Another NIJC client, Mauricio (pseudonym), fled gang violence and persecution he faced in El Salvador because of his sexual orientation, only to be detained for months upon arrival in the United States. He told BuzzFeed News that his continued detention had put him “on the edge of collapse,” and that he perceived “no changes in the system in favor of immigrants” under the new administration.

The Biden administration still has the opportunity to fulfill its commitments to address human rights abuses in the immigration system and end the U.S. government’s reliance on detention that leaves life-long scars for many. NIJC urges the administration to use the recommendations in this paper as a roadmap to begin the work of fully dismantling the U.S. immigration detention system.

NIJC submitted a memo to the administration that provides a detailed roadmap toward dismantling detention. The memo is available upon inquiry. For more information, email NIJC Director of Policy Heidi Altman.

Acknowledgments:

The following NIJC staff contributed to this white paper: Nayna Gupta, Jesse Franzblau, Mark Feldman, Mark Fleming, and Heidi Altman, Keren Zwick, and Tara Tidwell Cullen.