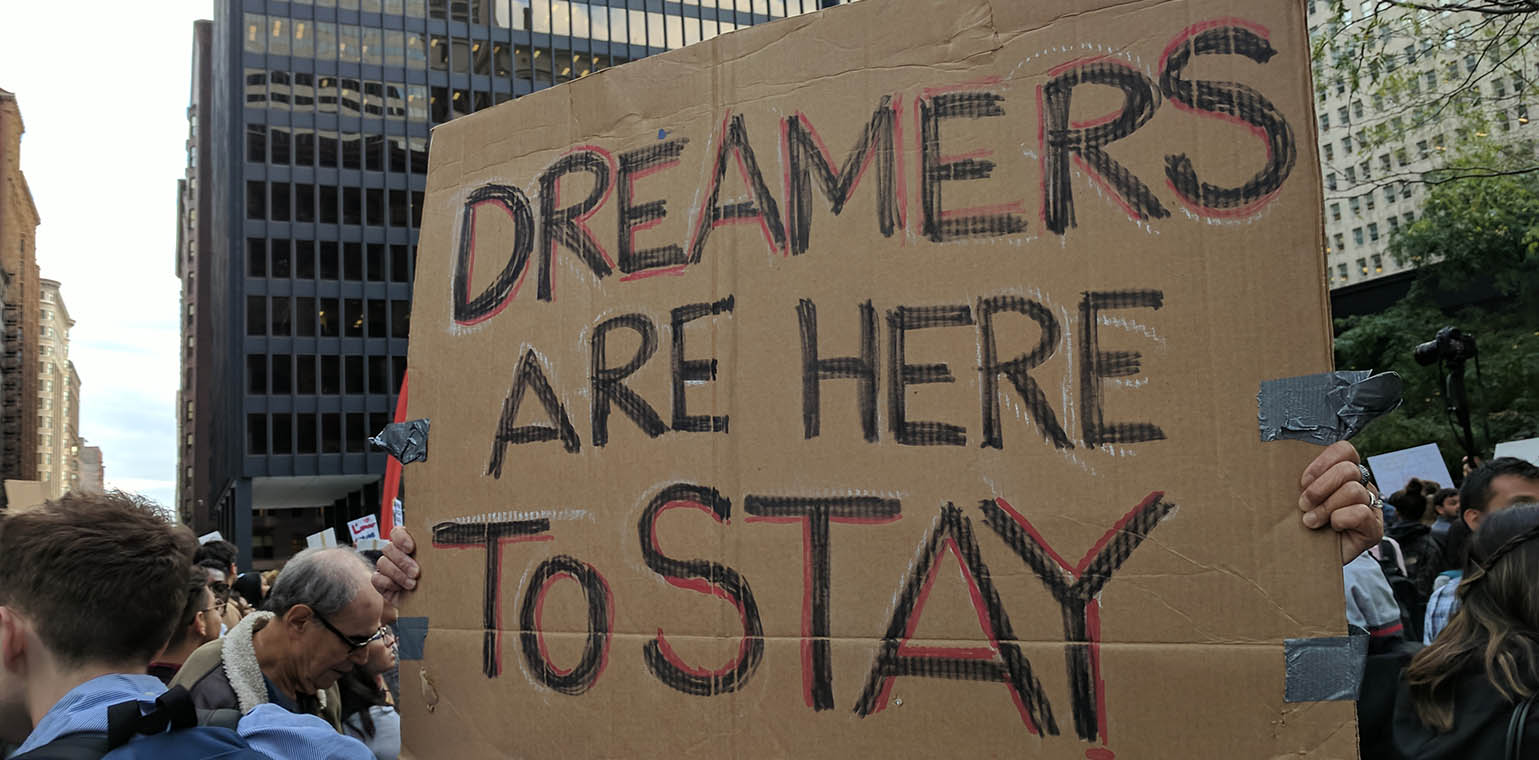

When the Supreme Court decides on the fate of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program — its ruling is expected any day — it will be evaluating the right to live and work in the United States for nearly 700,000 people around the country.

One of those people is Yash, a DACA recipient who has lived on the North Side of Chicago since 1997. When DACA was created in 2012, Yash was a senior in high school. He applied for and was granted DACA with the help of a National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC) clinic, and has continued to renew every two years at clinics hosted by NIJC and The Resurrection Project. Having DACA status has allowed Yash to mark regular milestones of growing up in the U.S.

“When I got my DACA, the first thing I did was I got a bank account, I got a debit card, got a driving permit which eventually became a drivers license, then I applied to a job at a big retailer, and I worked there for about 3 1/2 years,” Yash said. “I used that money that I earned to pay for community college, and then there I kept a high GPA so I could go to a four-year college and get a scholarship.”

Now, Yash works in sales for a manufacturer. All of these accomplishments were made possible by DACA. In fact, when an administrative mixup meant he lost status for a few months before college, he had to stop working until he was able to get the issue resolved. Yash is not the only person whose livelihood is contingent on his DACA status, which now is in the hands of the Supreme Court.

“Due to financial and personal circumstances, I needed to take care of my family.” Yash said, “ because I had the ability to work, I got my own apartment and provide as much as I can. If DACA is rescinded, it would be extremely financially difficult to keep up with the bills, to keep up with rent, to keep up with being able to take care of my family and to continue to work and make the same amount of money that I do.”

Yash was born in Europe, but because his parents were from India and moved to the United States shortly thereafter, he does not hold any European citizenship.

“If i were deported back to India, you’re sending me back to a place I’ve literally never been to, so that’s very scary for me,” Yash said.

Not being Latino, like the majority of DACA recipients, Yash said he has seen a different side of people’s reactions to the program.

“When people see me, and they see that I’ve been here for about 22 years, they don’t think that I’m undocumented, and when they find out, they’re shocked,” Yash said. “That just goes to show, number one, that this could happen to anyone, not just Latino people. The DACA program helps a lot of communities.”

Yash said he believes that the Supreme Court justices must take into account the lived experiences of DACA recipients, and ensure that there is some program in place to protect him and the hundreds of thousands like him whose livelihoods hang in the balance.

“I would advise them to listen to the stories of people who have DACA and understand the issues that they go through,” he said. “Additionally, I would tell them that any impending decision they make should be predicated on the idea that Congress makes some sort of action before DACA is eliminated because if it's not, it's just going to create chaos.”

Alejandra Oliva is the communications coordinator for NIJC.