The number of immigrants detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has reached unprecedented levels in recent months. NIJC’s Detention Project staff, who provide legal rights information and representation to immigrants and asylum seekers detained at county jails in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Kentucky, see first-hand the harm caused by such widespread and unnecessary incarceration of immigrants, including parents and young adults, and by the Trump administration’s refusal to release them while they seek legal protection. NIJC’s four-part series, “Getting Out,” highlights the experiences of NIJC legal staff and clients trapped in the system. In a prior story, Pani shared his experience of living in detention when he could not afford to pay his bond. This story focuses on what happened when he finally was released.

When the immigration judge granted Pani relief from deportation and a green card at the end of his hearing, he thanked her profusely over the video system the Chicago Immigration Court uses to conduct hearings with people in detention centers scattered throughout Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin, and Kentucky. He had not been allowed to participate in person in the hearing that would determine his fate. Instead, his attorney, the immigration judge, and the government attorney reviewed his case in a Chicago courtroom while Pani watched over video from Boone County Jail in Kentucky, pausing intermittently for an interpreter to explain the proceedings or relay a question from the judge in Spanish. I had worked with Pani, his family members, and his attorney to prepare his case for the immigration judge.

Prior to the hearing, we had reviewed with Pani the potential outcomes in his case. They ranged from accepting a deportation order to winning his case and being released from ICE custody. Even if he won, one worry loomed large: who would help him get home from Burlington, Kentucky to Russell Springs, Kentucky?

While only a three hour drive, Pani’s only support was his 17-year-old step-daughter. The mother of his three daughters had lost custody a year prior, and all three children were put in foster care after Pani was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Throughout the preparation of her father’s case, Pani’s daughter attended high school, worked 30 hours a week, and cared for her two younger sisters, always anxious at the thought of losing her dad. She had not been able to save enough money to drive to the jail for a visit during his six months in detention. Without any other family members to help contribute to gas or transportation, she called NIJC frequently to brainstorm different scenarios to get her dad from ICE custody back to his family.

Pani’s family’s situation was not unusual. Once people manage to get out of ICE detention, they face the challenge of getting home, with no money, and sometimes no knowledge of where they are.

Often, ICE will transfer immigrants to Chicago after they are ordered to be released from ICE custody. But after Pani won his case, we learned that ICE planned to release him directly from Boone County Jail. When planning for release from immigration custody, an individual’s legal representative often depends on family or community members to secure transportation, housing, and other basic necessities. In many cases, we purchase bus tickets to a city where a family member or friend can receive them. When ICE detention facilities are located in remote areas, like Boone County, immigrants and their legal representatives face a particular set of challenges.

Once we confirmed that Pani would be released, we scrambled to find bus routes and schedule a call with Pani to explain that he would need to take two local busses to the closest major city, Cincinnati, Ohio, before boarding a Greyhound bus that would drop him off in Bowling Green, Kentucky, about two hours away from his daughters. His step-daughter’s car had broken down the week before his hearing, so she was beholden to a friend to drive her to the Greyhound station to meet him and worried that their timing would not line up. Officers informed us that Pani would be released from the jail at 6:00 a.m. and provided a bus token to find a municipal bus to a larger bus station. The officers released him in the clothes he was wearing when first detained and with all of his personal property (including immigration paperwork, letters and notes) in a plastic bag and instructions to get to the nearest bus terminal written in English, even though he does not speak English. The bag also contained the cell phone he had on him when he was detained, but it had no charge.

About two hours after Pani’s release, we received a call from a good Samaritan who rode one of the city busses with Pani and was worried about his ability to navigate to the Greyhound station. We located Pani, eventually ordering a rideshare for him to the next bus stop. He arrived just in time to catch his final bus home.

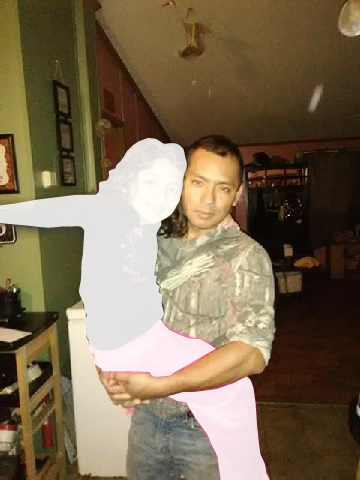

Nine hours after his release, Pani was reunited with his daughter.

Alice Thompson is a detention project coordinator at NIJC.