The number of immigrants detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has reached unprecedented levels in recent months. NIJC’s Detention Project staff, who provide legal rights information and representation to immigrants and asylum seekers detained at county jails in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Kentucky, see first-hand the harm caused by such widespread and unnecessary incarceration of immigrants, including parents and young adults, and by the Trump administration’s refusal to release them while they seek legal protection. NIJC’s four-part series, “Getting Out,” highlights the experiences of NIJC legal staff and clients trapped in the system.

When the judge announced that a $5,500 bond was all that stood in the way of Pani being reunited with his three daughters, his heart sank.

With their mother in and out of the home due to a drug addiction, the girls had been placed into foster care after Pani was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and sent to Boone County Jail in rural Kentucky. Since then, a lot of the family’s assets had been drained. Every week, his oldest daughter sent him a few dollars from her after-school job so that they could talk on the phone and he could buy a few things from the jail commissary. But Pani knew that the girls would not be able to raise that much money on their own. This meant that he had to stay in immigration detention until his case was resolved.

An indefinite stay in immigration jail was doubly daunting. Not only would he continue to be apart from his daughters, but he said he found the conditions at the jail horrifying. Pani was incarcerated for six months before he won his immigration case with the help of the National Immigrant Justice Center’s Detention Project. After Pani was home, he talked with NIJC staff about his life inside the jail.

“When I arrived, I slept on the floor for a week,” Pani said. “Many people don’t get a mattress because there are too many people, and for days they sleep only with their blanket on the floor. It’s cold there, very cold. When I arrived, you’re supposed to get things you need, like soap to shower, socks, and I didn’t get any of that.”

“Yo cuando llegué estuve en el piso durmiendo por una semana. Mucha gente no les dan un colchón porque ya la gente es mucha, y por unos días duermen solo con su cobija en el piso. Ahí esta frio, esta muy frio, y yo cuando llegue supuestamente te deben de dar tus cosas que necesitas como jabón para bañarse, calcetas, y a mi no me dieron nada de eso.”

While Pani was one of the lucky few to have legal representation, the jail did not always accommodate his conversations with his lawyer:

“Sometimes when my lawyer wanted to talk, they didn’t bring me [to the phone room],” Pani said. “If they did, they would take me out of my cell at 7, or before 7 in the morning, and they would put me in a little room all day, until 3 or 4 in the afternoon when they’d return me to my cell. I don’t know why they did it. One day I told them, ‘My lawyer won’t call me until 2 or 3, why are you taking me out of my cell now?’ And the guard said, ‘If you want to talk to your lawyer, then talk, if not I’ll cancel your appointment.’ They don’t give you an option.”

A veces si mi abogada quiere hablar, y no me van a traer, y si no, me sacaban de mi celda a las 7, o tantito antes de las 7 de la mañana, y me metian a un cuarto todo el dia, hasta las 3, 4 de la tarde me regresaban a mi celda. No se por que lo hacían. Un dia les dije, mi abogada no me va a hablar hasta las 2, 3, por que me llevan de mi celda desde ahorita? Y no, me dice, si quieres hablar con tu abogado, vas a hablar, y si no te cancelo la cita. Y no te dejan opción, tienes que ir.

Pani also witnessed the kind of medical neglect for which the ICE detention system is notorious. He picked up a particularly nasty case of foot fungus he suspects came from the bathrooms at the jail. This infection required several trips to the medical center to get a medication that actually worked. First, they gave him too small an amount of ineffective medication, and he was forced to go back again to get a stronger dosage, all the while the fungus worsened. In addition, Pani says he witnessed others’ suffering as well, including people going into what he believed was diabetic shock.

“I saw it about three times,” Pani said, “men who were there, about to die because their sugar levels were low. They sweat a lot, because the food there is not food for their sickness. When someone is sick, you have to yell, or call a guard on the phone, but you also can’t call on the phone, because they get annoyed. They say you shouldn’t call them for something like that, but I think it’s an emergency. It’s ugly in there. Now I’m a little traumatized, because I saw so much.”

“Hay gente que está enferma de diabetes y los dejan ahí solos y no los atienden. A mi me toco ver como 3 veces, de señores que están ahí apunto de morirse porque se les baja su azúcar. Sudán enserio, porque la comida que les dan no es una comida para su enfermedad. Cuando uno esta mal tienes que gritar o hablar con un guardia por teléfono, pero también no puedes hablar por teléfono porque se molestan, dicen que no debes de hablar por teléfono por algo asi, pero yo digo que es una emergencia. Esta feo ahi adentro. Me quede a la vez como un poco traumado, por que se ven muchas cosas.”

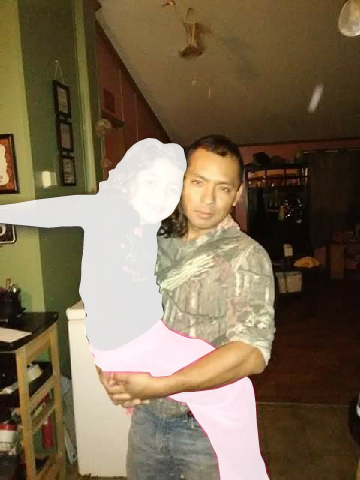

Eventually, Pani won his immigration case. Today, he is out of ICE jail, and is working to regain custody of his daughters. To do so, he needs a stable address and a job — both things he had and lost due to his unnecessary and prolonged time in ICE detention.

By setting a bond Pani had no hope of paying, the federal government cost taxpayers thousands of dollars (Boone charges the government $44.65 per day to jail someone in ICE custody) and caused long-lasting harm to Pani and his family.

“I’m out, now all I have to do is start again, little by little,” Pani said. “This is what happened in my case, there are a lot of people in that jail with different cases. It's sad, but it’s passed.”

Ya salí, ahora nada más me queda volver a comenzar de nuevo, pero poco a poco. Fue lo que me paso en lo que es mi caso, no sé, hay mucha gente ahí [en la cárcel] que tienen diferentes casos. Es algo triste pero ya, ya paso.

Alejandra Oliva is a communications coordinator at NIJC.

Cuando el juez anunció que una fianza de $5,500 era todo lo que quedaba en el camino de la reunificación de Pani y sus tres hijas, el corazón se le hundió a los zapatos.

Con su madre entrando y saliendo del hogar debido a una adicción de drogas, las niñas fueron puestas en cuidado temporal después que Pani fue detenido por el Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE, por sus siglas en inglés) y mandado a la Cárcel del Condado de Boone, en Kentucky rural. Desde entonces, muchos de los recursos de su familia han sido depletados. Cada semana, su hija mayor le mandaba algunos dólares de su trabajo de después de la escuela, para que pudieran hablar por teléfono, y para que pudiera comprar algunas cosas del comisario de la cárcel. Pero Pani sabía que las niñas no podrían hacer tanto dinero ellas solas. Eso quería decir que se tenía que quedar en detención de inmigración hasta que estuviera resuelto su caso.

Una residencia indefinida en cárcel de inmigración era doblemente difícil. No solo tendría que seguir estando separado de sus hijas, pero también dijo que encontró las condiciones en la cárcel horrorosas. Pani fue encarcelado por seis meses antes de ganar su caso de inmigración con la ayuda del Proyecto de Detención del Centro Nacional de Justicia para el Inmigrante. Después que Pani volvió a casa, hablo con personal de NIJC sobre su vida dentro de la cárcel.

“Yo cuando llegué estuve en el piso durmiendo por una semana,” dijo Pani. “Mucha gente no les dan un colchón porque ya la gente es mucha, y por unos días duermen solo con su cobija en el piso. Ahí esta frio, esta muy frio, y yo cuando llegue supuestamente te deben de dar tus cosas que necesitas como jabón para bañarse, calcetas, y a mi no me dieron nada de eso.”

Mientras Pani fue de los pocos que tenía representación legal, la cárcel no siempre facilitaba conversaciones con su abogado:

“A veces si mi abogada quiere hablar, y no me traían [al cuarto de teléfono,]” dijo Pani. “Y si no, me sacaban de mi celda a las 7, o tantito antes de las 7 de la mañana, y me metian a un cuarto todo el día, hasta las 3, 4 de la tarde me regresaban a mi celda. No se por que lo hacían. Un día les dije, mi abogada no me va a hablar hasta las 2, 3, por que me llevan de mi celda desde ahorita? Y no, me dice, si quieres hablar con tu abogado, vas a hablar, y si no te cancelo la cita. Y no te dejan opción, tienes que ir.”

Pani también fue testigo del tipo de negligencia médica por la cual el sistema de detención de ICE es notorio. Pescó un tipo de hongo en el pie particularmente malo que el sospecha vino de los baños en la cárcel. Esta infección requirió varios viajes al centro médico para conseguir una medicina que le servía. Primero, le dieron muy poco de una medicina ineffectual, y fue forzado regresar a conseguir una dosis mas fuerte, todo mientras empeoraba el hongo. Adicionalmente, Pani dice que fue testigo del sufrimiento de otros, también, incluyendo gente entrando a lo que él cree que fue shock diabetico.

“Hay gente que está enferma de diabetes y los dejan ahí solos y no los atienden,” dijo Pani. “A mi me toco ver como 3 veces, de señores que están ahí apunto de morirse porque se les baja su azúcar. Sudán enserio, porque la comida que les dan no es una comida para su enfermedad. Cuando uno esta mal tienes que gritar o hablar con un guardia por teléfono, pero también no puedes hablar por teléfono porque se molestan, dicen que no debes de hablar por teléfono por algo así, pero yo digo que es una emergencia. Esta feo ahí adentro. Me quede a la vez como un poco traumado, por que se ven muchas cosas.”

Eventualmente, Pani ganó su caso de inmigración. Hoy, está fuera de la cárcel de ICE, y está trabajando para poder conseguir custodia de sus hijas. Para hacerlo, necesita tener una dirección estable, y un trabajo--ambas cosas que tenia y perdió debido a su innecesario y prolongado tiempo en detención de ICE.

Al poner una fianza que Pani no tenía esperanza de pagar, el gobierno federal le costó miles de dólares a contribuyentes (Boone le cobra $44.65 por día al gobierno federal para encarcelar a alguien en custodia de ICE) y causó daño a largo plazo a Pani y a su familia.

“Ya salí, ahora nada más me queda volver a comenzar de nuevo, pero poco a poco,” dijo Pani. “Fue lo que me paso en lo que es mi caso, no sé, hay mucha gente ahí [en la cárcel] que tienen diferentes casos. Es algo triste pero ya, ya paso.”

Alejandra Oliva es la coordinadora de comunicaciones en NIJC.