The detention system the U.S. government uses to lock up immigrants and refugees is intentionally difficult to understand. It involves a network of government and privately operated detention centers and jails spread across the country and four different federal agencies.

Immigrants are taken into government custody after arriving at the border or after being arrested in the interior of the country. For individuals who cross into the U.S. through the southern border, their first encounter with immigration enforcement is with Customs and Border Protection (CBP), an agency under the jurisdiction of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). A federal court settlement limits children's time in CBP custody to 72 hours, and there are recommended time limits for adults as well, but violations are common and adults often languish for days or weeks. CBP detention facilities are usually near the border, and can include both small outposts and the enormous “processing centers” like those at McAllen, Texas, and San Ysidro, California.

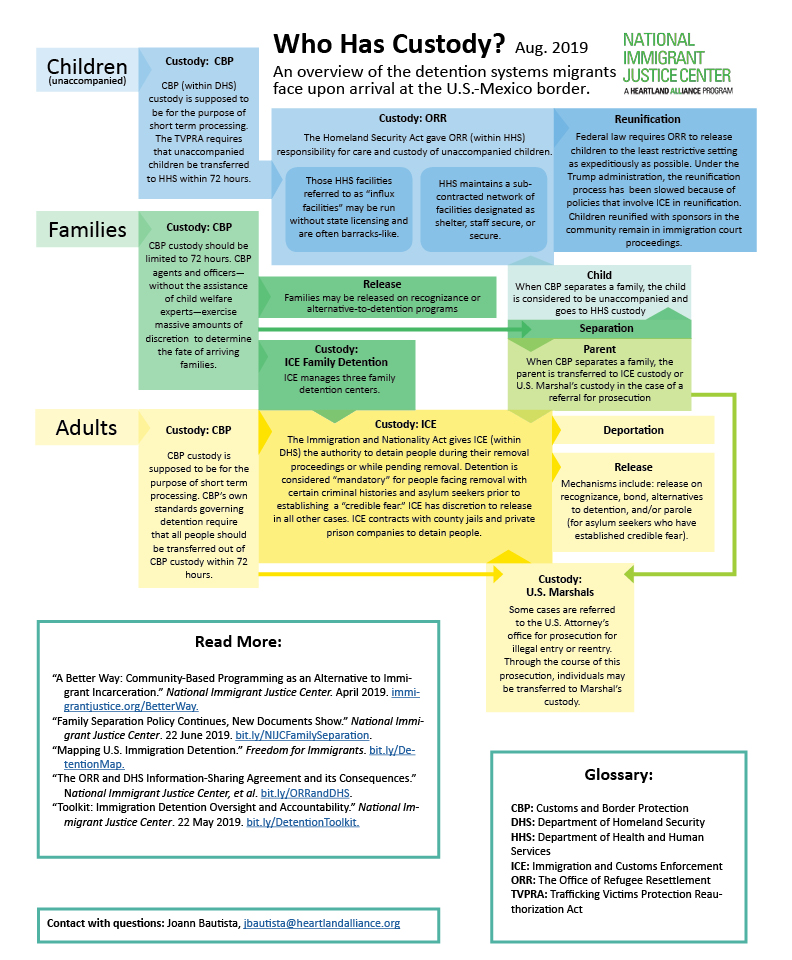

From there, things get a lot more complicated and the journey through the detention system depends on whether the person is an unaccompanied minor, an adult or a family composed of both adults and children.

Unaccompanied Children

After a child is picked up by CBP or DHS’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and determined to be an unaccompanied child, they are transferred into the custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which is under the Department of Health and Human Services. Children are supposed to remain with ORR until a family member or guardian “claims them,” something that has become much more difficult since ICE has inserted itself in the reunification process. While some children are fortunate enough to be reunited with family, others are not as lucky. When ORR fails to make arrangements, either reunification or alternative placement, for a child who is about to turn 18, the child is often transferred into adult ICE custody on their 18th birthday.

Families

Despite the supposed termination of the family separation policy in June 2018, families crossing the border are still being separated for vague or baseless reasons. When this happens, children are designated “unaccompanied” and are placed into ORR shelters, while adults are transferred into ICE or Department of Justice U.S. Marshal custody. If families are kept together, they may be released from CBP custody to await their proceedings, or put into one of three detention centers ICE maintains to hold family units.

Adults

Adults traveling alone and the parents of separated children face a dual track after CBP custody: some are transferred directly into ICE custody, and some may be transferred into U.S. Marshal’s custody to be criminally prosecuted for entering or re-entering the U.S. without a valid visa or without undergoing inspection at a port of entry. Criminal prosecutions often happen quickly, after which a person is moved into ICE custody. ICE custody can mean being locked up in places like Cibola County Correctional Center in New Mexico (a privately owned prison), or Boone County Correctional Facility in Kentucky (a county jail). From ICE custody, people are either deported or released through bond programs, on their own recognizance, or placed in alternative-to-detention programs that require surveillance like ankle monitoring and telephonic check-ins.

While immigration enforcement on the southern border often gets more attention, ICE also targets people throughout the interior of the country, including new arrivals and people who have lived in the U.S. for decades. Sometimes these arrests are the result of a large-scale workplace raid, other times they begin with a simple traffic stop. The number of individuals locked in ICE detention centers has been growing at an unprecedented rate, recently reaching 55,000 people each day.

This system is meant to be confusing, difficult to report on and access from the outside. At NIJC, as part of the Defund Hate Coalition, we’re working to end detention and move toward a better way of thinking about immigration: a community-supported, evidence-based approach of welcoming people into the country that doesn’t involve punishment.

View our new infographic, "Who Has Custody?"

Joann Bautista is the policy associate and Alejandra Oliva is the communications coordinator at NIJC.