This case was formerly known as Herrera Cardenas v. ICE

In April 2022, NIJC and Sidley Austin LLP sued Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and multiple county officials from Clay County, Indiana, on behalf of people detained by ICE at the Clay County Jail. Lead plaintiffs, Cristhian Herrera Cardenas, Maribel Xirum, Javier Jaimes Jaimes, and Biajebo Brown Toe, seek to represent a class of all current and future individuals held in this facility by ICE.

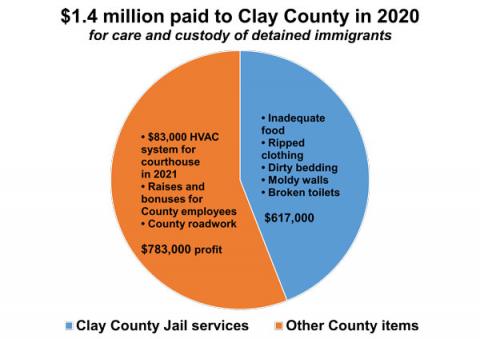

Plaintiffs argue that Clay County is illegally profiting from the detention of noncitizens at the jail, all while ICE turns a blind eye to the jail’s blatant violations of federal detention standards and ignores the county’s misuse of federal funds. ICE pays Clay County over $1.4 million dollars per year to detain noncitizens, and immigration law plainly states that this money must be used for the care and custody of those in detention. Instead, the county has used ICE as a cash cow, spending hundreds of thousands of federal dollars on unrelated county expenses. In 2021, for example, Clay County used this money to purchase an $83,000 air-conditioning system for its courthouse. The county also gave its employees raises and bonuses, and it publicly admits that this money allows the county to avoid raising taxes.

While the county profits, plaintiffs and others detained by ICE suffer in grossly inadequate conditions at the jail. By any reasonable measure, the jail does not provide basic levels of care. As a result, people detained by ICE:

- Receive insufficient food and hygiene supplies, so they must buy these items at the commissary when they can afford them;

- Wear used, dirty clothing—including used underwear—and lack access to sufficient layers to keep them warm;

- Sleep in overcrowded cells, sometime on plastic mattresses on the floor called boat beds, and with sheets that are worn thin and have holes in them;

- Go to the bathroom and shower with limited or no privacy and thus must use their worn-out sheets as make-shift privacy screens;

- Clean their cells with toilet paper and a makeshift mix of their own soap, shampoo, and toothpaste because the jail provides inadequate cleaning supplies;

- Are routinely denied access to critical services, like outdoor recreation, use of a law library, mental-health counseling, religious ministry, the ability to speak to a medical professional through an interpreter, and the ability to make international calls to family members who might be in a position to support a legal defense.

Alongside these injustices, the jail is rundown and understaffed. The walls are riddled with mold and graffiti, the air is dusty, and the showerheads barely work. The toilets, which are already insufficient in number, are broken for weeks at a time. There are no medical professionals available on the weekends, and access to specialty medical care is likely to be delayed by weeks.

Plaintiffs argue that these and other conditions violate the national standards that ICE detention facilities must satisfy, the Performance-Based National Detention Standards (PBNDS). Indeed, the facility failed its inspection in May 2021 because of poor sanitation, overcrowding, deficiencies in medical care, and other failures. Following this failure ICE knows that the jail is not meeting the required standards and it likewise knows that many of these deficiencies have not been addressed. Yet, ICE gave the Clay County Jail a passing score on its most recent inspection in December 2021 . ICE did this, not because the jail had improved, but because it was trying to avoid losing the bed space, which would have been required if the jail failed two consecutive inspections.

See more documents obtained via open-records requests which are cited in this complaint.

It was only thanks to discredited inspections practices that the jail was able to pass the December 2021 inspection. For example, ICE relied on a third-party contractor called Nakamoto, whose inspections have been described as “very, very, very difficult to fail” and “useless,” even though Congress instructed ICE to conduct its own inspections rather than relying on this contractor. On top of that, ICE gave the jail more than a month’s notice before the inspection and allowed inspectors to do critical portions of the inspection remotely and without interviewing detained individuals.

Plaintiffs call for the Court to rule that conditions at the jail do not satisfy ICE’s detention standards and therefore cannot continue to house noncitizens. They also argue that defendants are breaking the law by misallocating federal payments intended for the custody and care of noncitizens detained at Clay County Jail for other county services.

The Plaintiffs

Baijebo Toe is a 37-year-old Liberian man. He entered the United States in 1994 as a refugee, when he was nine years old. Among other issues, he has been severely affected by the Jail’s inadequate mental health services. He has been struggling with symptoms of depression and requested to speak with a therapist several months ago. Instead, the Jail has only offered him medication and has yet to allow him to speak with a therapist. Mr. Toe believes that his depression has been exacerbated by the lack of outdoor recreation or even windows.

Maribel Xirum is a 46-year-old Mexican woman who has lived in the United States since she was four years old and has multiple U.S. citizen children. Throughout her detention at Clay County Jail, she has been shocked by the conditions, particularly the inadequate and delayed medical care she has received. For instance, although Ms. Xirum complained of severe tooth pain to medical staff, she had to wait three weeks before they finally took her to a dentist. The dentist had to extract her tooth, which at that point had become infected. On top of delayed medical care, Ms. Xirum has witnessed sexual harassment in the women’s unit.

Javier Jaimes Jaimes is a 32-year-old man from Mexico. He moved to the United States when he was 18, and he has a six-year-old U.S.-citizen daughter. He was previously deported to Mexico but has returned to the United States in search of protection after being kidnapped and tortured by cartels in that country. Since his arrival at Clay County Jail in January 2022, he has received inadequate medical care. Guards have provided him with pills that were different in color and form from his prescribed medication. With no Spanish-speaking staff at the jail, he has had to rely on other detained immigrants to explain these sorts of issues. His four-person cell often has extra people sleeping on the floor in “boat beds.” When the cell toilet stopped working and spilled wastewater into the cell, the jail delayed its repair.

Related Documents

Court's Decision on Second Motion to Dismiss as to Federal Defendants (August 8, 2024)

Court's Decision on First Motion to Dismiss (March 29, 2023)

ICE Motion to Dismiss Reply (Sept. 14, 2022)

Clay County Motion to Dismiss Reply (Sept. 14, 2022)

Plaintiffs' Omnibus Opposition to Defendents' Motions to Dismiss (August 26. 2022)

Federal Defendants Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss (July 22, 2022)

Clay County Defendants Brief in Support of Motion to Dismiss (July 15, 2022)

Filed complaint (April 25, 2022)

Featured Media

NIJC Press Release: Federal Court Rules For Case To Move Forward In Challenging ICE’s “Extreme” Abdication Of Responsibility Over Misappropriated Detention Funds (August 2024)

NIJC Press Release: Federal Court Allows Case Challenging ICE Detention Inspection Process to Proceed (March 2023)

The Indiana Lawyer: Federal judge allows part of lawsuit against ICE to continue, dismisses claims against Clay County (March 2023)

Injustice Watch: Clay County using ICE detention as 'cash cow': Lawsuit (June 2022)

NIJC Press Release: Immigrants Detained in Indiana Jail Sue County and Federal Governments for Illegally Relying on ICE Contract as a “Cash Cow” While Ignoring Human Suffering Inside (April 2022)

NIJC Blog Post: Confronting the immigration detention system | National Immigrant Justice Center (April 2022)