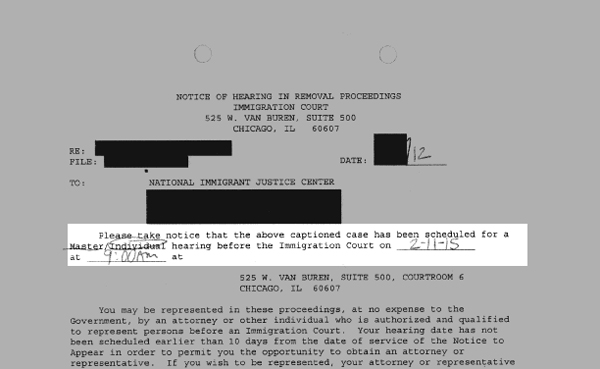

Michael* fled to the United States after the Eritrean government imprisoned and brutally tortured him for speaking out against Eritrean military policies. When he reached the United States border in late 2010, he immediately requested asylum. His first “status” hearing before the immigration court was scheduled for March 2012. Michael hoped that after his status hearing, he would soon be able to explain to the immigration judge why he was afraid to return to Eritrea and obtain asylum in the United States. But at his March 2012 hearing last week, the immigration judge scheduled him for a merits hearing in February 2015—four and a half years after he first requested asylum.

Michael is allowed to remain in the United States while he waits for his court hearing, but his lack of formal immigration status means he must spend the next three years in limbo. As Michael said at the hearing, “It is very hard to feel comfortable, knowing you still have a hearing in your case.”

Waits of one and a half to three years for hearing dates in the Chicago Immigration Court have become common, despite four additional judges joining the court in 2010. The Obama administration’s enforcement policies have placed record numbers of people in removal proceedings, minimizing any positive impact these new judges would otherwise have had on the court’s severely backlogged docket.

Nationally, the problem is immense. The number of cases pending in the immigration courts reached a record high of 275,316 in May 2011, with an average wait time of about 16 months. Thousands of people are in situations similar to Michael’s.

For asylum seekers, a two-to-three-year hearing delay can cause extreme mental, physical, and financial anguish. Many asylum seekers flee their counties of origin without any resources. Because it is difficult, if not impossible, for asylum seekers to obtain work authorization, they often depend on the charity of family, friends, and religious organizations until they obtain status and are able to provide for themselves. This support wanes, however, when hearings are delayed for years and some asylum seekers end up homeless and unable to obtain basic necessities. Some NIJC clients have contemplated risking their lives and returning to countries of persecution to escape the extreme poverty they experience while awaiting an answer on their asylum applications.

Many asylum seekers leave behind spouses and children when they flee to the United States—expecting to be reunited when they win asylum. As immigration court hearing delays increase, they face lengthy separation from their families, many of whom remain in danger. NIJC recently obtained asylum for a woman whose case had been continued from 2006 until 2012. While she waited for a decision in her case, her young children remained in dangerous conditions in her home country. The client’s daughter was abused by another family member and her sons had to stop attending school because of gang violence. By the time she received asylum, she had not seen her children for more than six years.

Finally, the hearing delays at the Chicago Immigration Court have a detrimental impact on an asylum seeker’s ability to obtain pro bono representation and access to justice. NIJC provides representation for more than 200 asylum seekers per year through a network of more than 1,000 pro bono attorneys in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana. Without these pro bono attorneys, many asylum seekers would be unable to obtain representation, significantly decreasing their likelihood of success. The extreme hearing delays at the Chicago Immigration Court make it difficult for pro bono attorneys to commit to handling these cases. NIJC now struggles to find attorneys willing to take them on.

As long as the Obama administration continues to increase immigration enforcement without increasing resources for the immigration court system, hearing delays will only worsen. NIJC has proposed key reforms that would help make the court system more efficient, including improving access to counsel for immigrants and investing in staff and resources which would help judges cope with the excessive caseloads. The most effective solution, however, would be for the administration to stop clogging the courts with the deportation proceedings of men, women, and children who have been swept up in the expanding immigration dragnet and allow the courts to timely adjudicate the cases of asylum seekers.

*Psuedonym used to protect the client's privacy