NIJC Freedom of Information Act Litigation Reveals Systemic Lack of Accountability in Immigration Detention Contracting

August 2015 Report

I. Executive Summary

The National Immigrant Justice Center’s (NIJC’s) three-year Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) litigation has resulted in the most comprehensive public release to date of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) immigration detention center contracts and inspections. The thousands of pages of documents provide an unprecedented look into a failed system that lacks accountability, shields DHS from public scrutiny, and allows local governments and private prison companies to brazenly maximize profits at the expense of basic human rights.

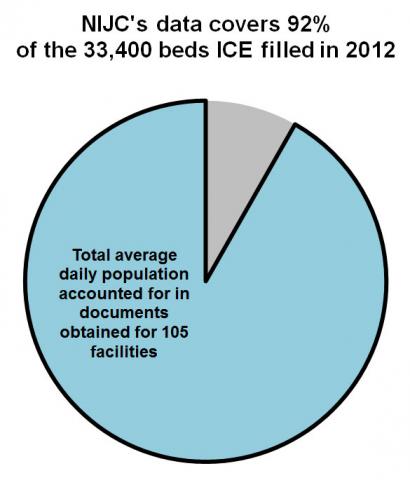

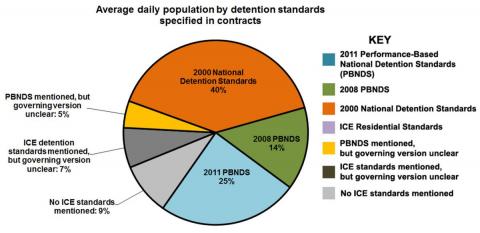

NIJC’s pursuit of transparency and accountability began in April 2011 with a FOIA request seeking all U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facility contracts, as well as inspection reports dating back to 2007. Notwithstanding President Obama’s 2009 directive to increase government transparency, it took four years, one federal lawsuit, two depositions of ICE officers deemed experts in immigration detention contracting and inspections, and a federal court order to obtain documents for more than 100 of the country’s largest detention facilities. The average daily population for these facilities represents approximately 92 percent of the 33,400 detention beds ICE maintained on an average day in 2012 (the most recent year for which NIJC obtained documents). (See Fig. 1)

- The immigration detention contracting process is convoluted and obscure, suffering from a significant lack of uniformity in how contracts are created, executed, and maintained.

- There is a lack of consistency and clarity as to which detention standards govern which facilities.

- Forty-five facilities operate with indefinite contracts, mostly under outdated standards.

- Tracking the taxpayer dollars ICE pays to local and private contractors to detain immigrants is daunting, and for some facilities, nearly impossible.

- The practice of contracting and subcontracting with private entities shields many ICE detention facilities from public (taxpayer) scrutiny.

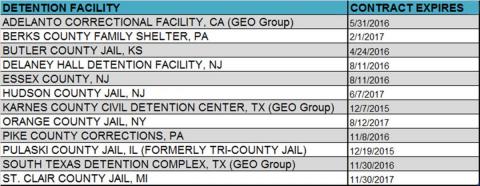

- At least 12 contracts will expire in the next three years, providing an opportunity for advocates to raise questions about the efficacy of keeping these facilities open and ensure any modifications or extensions contain robust standards.

To address these issues, NIJC calls on ICE to:

- Provide public access to information regarding the detention center contracting process.

- Require that all facilities adhere to the 2011 Performance-Based National Detention Standards (2011 PBNDS), the most-current and robust set of ICE detention standards, without further delay.

- End the practice of entering into indefinite contracts and revisit any existing contracts which do not contain explicit renegotiation dates.

- Refrain from entering into contracts agreeing to minimum bed guarantees.

- Throughout the contracts negotiation process for individual detention facilities, engage with legal service providers, faith groups, and other local and national non-governmental organizations that visit facilities, to address human rights and due process issues they observe.

NIJC calls on Congress to increase government transparency and improve oversight of ICE by passing the following two pieces of legislation:

- Accountability in Immigration Detention Act, sponsored by Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA)

- Protecting Taxpayers and Communities from Local Detention Quotas Act, sponsored by Reps. Ted Deutch (D-FL), Bill Foster (D-IL), and Smith

II. Obama’s Unfulfilled Promises of Transparency and Reform

On January 21, 2009, President Obama’s first full day in office, he announced his intent to set an open tone for the federal government under his administration. In a memorandum encouraging greater government transparency and accountability, the president directed then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder to issue new FOIA guidance to all executive departments and agencies.

About eight months later, the Obama administration announced reforms to the immigration detention system, including ways to reduce detention, standardize contracts, and implement more oversight over facilities using a more “civil” model. Advocates championed these goals, which also were supported by an expert consultant hired by the Obama administration to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the detention system.

Six years later, the sprawling DHS detention system has only grown farther from those civil detention reform goals. Instead of reducing detention, the administration now incarcerates women and children who flee to the United States seeking protection from persecution. While NIJC’s FOIA did not specifically request family detention center contracts, two of which did not exist in 2011, recent reports have questioned the morality of detaining families and the manner in which family detention center contracts are negotiated. This report does not address family detention, however many of the concerns arising from the detention of families are similar to concerns with the entire immigration detention system, including reports of unreasonably high bonds (particularly for asylum seekers), hunger strikes, deaths, suicide attempts, and inadequate medical care.

ICE remains as secretive as ever about its detention contracting and inspection processes. ICE does not proactively share information about contracts and inspections and has done so only when forced via FOIA requests. The little information ICE does release pursuant to FOIA lawsuits is far from transparent. For example, most of the contracts and inspections posted on the agency’s FOIA Library website are outdated. ICE does not publicly share which facilities are open or closed. Moreover, the increased use of private contractors and sub-contractors further obfuscates how billions of taxpayer dollars are distributed and used to negotiate these contracts. Corporations take advantage of their private entity status to invoke redactions regarding funding allocations and avoid direct liability for sub-standard conditions.

III. Understanding the Contracts

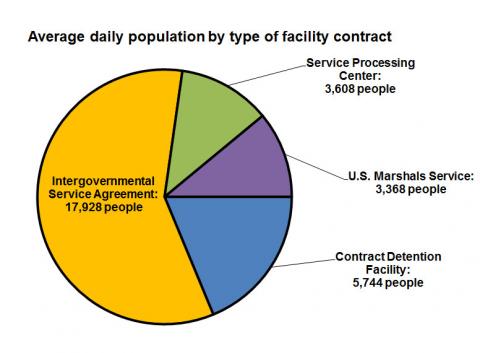

ICE divides its detention facilities into four categories, which dictate the execution and often the terms of each contract (See Fig. 2):

Contract Detention Facilities (CDFs): Facilities owned and operated by private corporations that contract directly with ICE. ICE officials have stated that these facilities, often built just to detain immigrants, are subject to the 2011 PBNDS.

A myriad of complex federal contracting protocols, statutes, and regulations, most notably the Federal Acquisition Regulation, govern CDF contracts. Congress’ appropriations process allocates funds to pay the contractors and contract line item numbers (referred to as “CLIN” in the contracts) track facilities’ expenses and how money is paid. As a result, deciphering how much taxpayers pay for these facilities, and how these private contractors allocate money to run the detention centers, is nearly impossible for anyone who is not an expert in government appropriations and contracting.

Service Processing Centers (SPCs): Six facilities directly owned and operated by ICE, though ICE hires contractors to handle many services, including administration of some facilities. NIJC received one SPC contract, between ICE and the Alaska Native Corporation Ahtna Technical Services, Inc., to administer Port Isabel Service Processing Center in Texas.

Intergovernmental Service Agreements (IGSAs): Facilities owned and operated by local governmental entities, most often county or city governments. Many local governments in turn subcontract with private corporations to administer and provide services. While private corporations have garnered the most attention for warehousing immigrants for profit, NIJC has found that even local governments seek to maximize profits from the detention space they rent to ICE. At some facilities, such profit motives have resulted in cost-cutting on a range of basic needs for immigrants, such as medical care, food, and hygiene products. Other county governments have hired consultants to navigate the obscure process of negotiating higher per diem rates. Some IGSA facilities hold individuals in ICE custody exclusively and are referred to as “dedicated IGSAs” or “DIGSAs.” NIJC did not discern any particular differences between IGSA and DIGSA facility contracts. In fact, the contracts themselves do not denote whether the facility is a DIGSA.

U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) Intergovernmental Agreements (IGAs): Facilities under contract with the Department of Justice’s U.S. Marshals Service. Typically, these contracts pre-date the 2003 creation of DHS, and continue to be renewed via the U.S. Marshals, though subsequent amendments (also referred to as “modifications”) list ICE as a party to the contracts. Initially, in NIJC’s litigation, ICE claimed not to have USMS contracts under its “custody or control,” but began producing these contracts following a court order. Because many of the USMS IGAs were initiated before the creation of the first ICE detention standards, they often do not reference clear applicable standards for detaining immigrants. Further, most of the USMS IGAs are of indefinite duration.

IV. A System in Disarray: NIJC’s Review of 94 Detention Center Contracts

Where possible, NIJC has annotated the following in the contracts posted at immigrantjustice.org/transparencyandhumanrights: 1) type of contract, 2) per diem rate, 3) contract effective and expiration dates, and 4) applicable ICE detention standards. We also have noted any additional specific standards incorporated into the contracts, such as DHS Prisoner Rape Elimination Act regulations, various versions of ICE directives on Sexual Abuse and Assault Prevention and Intervention, and ICE’s 2011 Review of the Use of Solitary Confinement.

NIJC’s months-long review of the thousands of pages of contract documents revealed:

- The immigration detention contracting process is convoluted and obscure. Specific contracts and the ICE contracting officer deposition show a significant lack of uniformity in how contracts are created, executed, and maintained, particularly among facilities that operate under IGSAs. This disarray presented enormous problems and delays as ICE struggled to respond to NIJC’s FOIA request. For example, ICE frequently grouped documents from county facilities in different states together as one facility because the counties had the same name — a filing error that the GAO said was also responsible for ICE misdirecting payments to the wrong contractors.

- There is a lack of consistency and clarity as to which detention standards govern which facilities. (See Figs. 3 and 4) Only 12 contracts (representing about 27 percent of the detention population covered by NIJC’s report), explicitly subject facilities to the 2011 PBNDS. While imperfect and based on a correctional rather than civil detention model, this set of standards provides the most robust protections for detained immigrants. A large number of contracts cite only the weaker and outdated ICE 2000 National Detention Standards or 2008 PBNDS, and several other contracts only generally reference “ICE detention standards” or do not mention any ICE standards at all. Many refer contractors to web links to obtain more information about governing ICE detention standards, but those web links mostly are broken and lead to error pages on ICE’s website. The GAO reported that, to avoid opening full IGSA contracts to negotiation, ICE sometimes obtains a facility’s agreement to be inspected according to a more recent set of standards without explicitly incorporating the new standards into the contract. This practice makes it nearly impossible to know which standards apply to specific facilities, or how ICE informs facilities when they are subject to an updated set of detention standards. According to the GAO report, ICE officials “stated that they planned to request that all facilities with an ADP [average daily population] of 150 detainees or greater adopt the 2011 PBNDS by end of fiscal year 2014.” NIJC does not know whether the agency followed through with this promise.

- Forty-five facilities operate with indefinite contracts. Most of the facilities that operate under indefinite contracts do not have ICE detention standards incorporated into their contracts or operate under the 2000 National Detention Standards. In other words, no renegotiation is built into the contracts to provide an opportunity to incorporate more updated standards or to question the efficacy of the facility’s use.

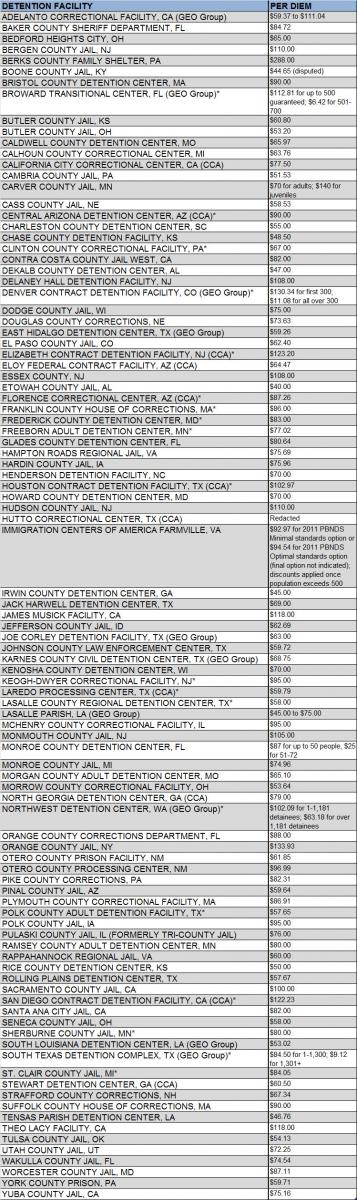

- Tracking the costs of immigration detention is daunting. Per diem payments range from $40 to $133 per individual depending on the facility, but the formula used to calculate those rates and what they include vary significantly. For example, some contracts include guards, transportation, and other services within the “per diem” rate, while other contracts list such services as separate line items. In 2014, the GAO found that even ICE’s internal systems to track costs at each facility were inadequate “because of errors in how ICE field office personnel enter data … and limitations in the system.”

(Download a PDF of this per diem chart)

- The practice of contracting and subcontracting with private entities shields the DHS immigration detention system from public (taxpayer) scrutiny:

- While nine of the contracts NIJC received are between ICE and private prison companies, based on a review of the CCA and GEO Group websites at least 13 other facilities are contracted to local governments which then subcontract the detention centers’ administration to those companies. While some IGSA contracts contain clauses binding subcontractors to their terms, the subcontractor relationships often are not articulated in the contract language.

- Almost all per diem rates are redacted from private contracts received by NIJC, under the guise of a FOIA exemption that protects “[t]rade secrets and commercial or financial information obtained from a person and privileged or confidential.” However, ICE failed to redact those per diems from the cover pages of their inspection reports, which allowed NIJC to create a comprehensive list of per diem rates for 98 detention centers. (See Fig. 5) The inspections will be published later this year.

- At least 12 contracts will expire in the next three years. The contract negotiations could provide an opportunity for advocates to raise questions about the efficacy of keeping these facilities open and ensure any modifications or extensions contain robust standards. (See Fig. 6)

Fig. 6: Detention facility contracts expected to expire within the next three years

V. Transparency is a Human Rights Issue

ICE’s transparency problem is a human rights problem. As Grassroots Leadership found in its April 2015 report, when the U.S. government allows private companies and local governments to profit by warehousing people far from public scrutiny and government accountability, no matter how “civil” the detention facilities appear, the men, women, and children in custody become little more than inventory.

A 2015 report by the Detention Watch Network and the Center for Constitutional Rights highlights the “guaranteed minimums” contained in some ICE detention contracts, which bind the government to pay for a minimum number of detention beds and places pressure on immigration officials to incarcerate immigrants to meet those quotas. The experiences immigrants describe once they are within the walls of the isolated detention centers show how the system reduces human lives to mere fodder in a business transaction.

VI. Recommendations

- Most-current ICE contracts

- Details on what facilities ICE uses and who operates them, contract awards, per diems and capacity at each facility, and the average daily population of individuals detained in each

- Information about which standards apply to each detention center, and how ICE enforces those standards

2. Require all detention facilities to immediately adhere to the 2011 Performance-Based National Detention Standards, and terminate contracts for facilities which are unable or unwilling to meet these standards.

3. End the practice of entering into indefinite contracts and revisit any existing contracts which do not contain explicit renegotiation dates.

4. Refrain from contracting with private corporations or other entities that require guaranteed payments for a minimum number of immigration detention beds, and modify existing contracts to remove guaranteed bed minimum payments. If the contractor is unwilling to make such a modification, ICE should terminate the contract.

5. Throughout the contracts negotiation process for individual detention facilities, engage with legal service providers, faith groups, and other local and national non-governmental organizations that visit facilities, to address human rights and due process issues they observe.

NIJC calls on Congress to increase government transparency and improve oversight of ICE by passing the following two pieces of legislation:

1. Accountability in Immigration Detention Act, sponsored by Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA): Originally introduced in 2014 and re-introduced in 2015, this bill establishes minimum detention standards to ensure that everyone in immigration detention is treated humanely. The bill requires all detention facilities to comply with the most recent detention standards and subjects non-compliant facilities to “meaningful” financial penalties. In addition, the bill mandates public disclosure of all contracts, memoranda of agreement, evaluations, and reviews related to immigration detention facilities.

2. Protecting Taxpayers and Communities from Local Detention Quotas Act, sponsored by Reps. Ted Deutch (D-FL), Bill Foster (D-IL), and Smith: Introduced in 2015, this bill prohibits ICE from entering into contracts that provide detention centers with prepaid, guaranteed numbers of filled beds each day.

VII. Acknowledgments

VIII. Corrections

- The California City contract cites the 2008 PBNDS, not the 2011 PBNDS

- Irwin County Detention Center is a USMS facility, not IGSA

- Utah County Jail's contract cites the 2008 PBNDS

- A modifcation to the Houston Contract Detention Center's contract cites the 2011 PBNDS, not 2000 NDS