This post is the second in a new series by NIJC's detention team in which NIJC staff, clients, and volunteers will share their unique perspectives on immigration stories that do not always make the news. We invite readers to share their own experiences and reactions in a moderated discussion in the comments section.

I began my legal career working with Guatemalan asylum seekers looking to become lawful permanent residents of the United States. In working with this community, I heard stories time and again about loved ones who had been disappeared and saw firsthand how having a husband, son, or daughter disappeared can create a special kind of guilt, fear and grief. Working with detained immigrants many years later, I cannot help but notice parallels between individuals who were purposely disappeared in 1980s Guatemala and individuals who disappear when taken into ICE custody – mainly in the ways that family members left behind are affected by not knowing the immediate fate of their loved ones.

I began my legal career working with Guatemalan asylum seekers looking to become lawful permanent residents of the United States. In working with this community, I heard stories time and again about loved ones who had been disappeared and saw firsthand how having a husband, son, or daughter disappeared can create a special kind of guilt, fear and grief. Working with detained immigrants many years later, I cannot help but notice parallels between individuals who were purposely disappeared in 1980s Guatemala and individuals who disappear when taken into ICE custody – mainly in the ways that family members left behind are affected by not knowing the immediate fate of their loved ones.

When an individual is detained by ICE, he or she can in fact be disappeared. It can take family members days, or in some cases weeks or even months, to locate loved ones arrested by ICE. Sometimes, a family does not learn of a loved one’s whereabouts until that person calls home after they are deported.

Locating a loved one relatively quickly does not necessarily lessen the trauma of witnessing the arrest in the first place. Take the case of Viviana and Martin*—mother and son. ICE officers came to their home and misled Viviana into believing that they were local police officers who only wanted to talk to Martin. They convinced Viviana to call her son home. She was devastated after witnessing the officers take her son into custody without further explanation. Martin—who had just turned 18,had diagnosed learning disabilities, had no previous encounters with the immigration authorities, and had engaged in no wrongdoing—was taken away, surrounded by armed men, while Viviana watched helplessly. The hours following Martin’s arrest were harrowing. Viviana spent that night calling every police station in town, only to be told there was no one by her son’s name in custody. Throughout the ordeal, Viviana was overcome with grief at the thought that she had turned in her own son.

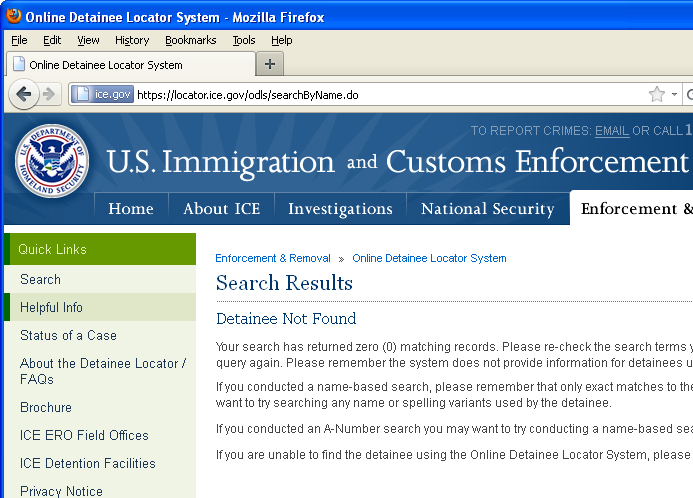

There are countless stories like Viviana and Martin’s—sometimes it’s mothers, sometimes fathers, sons or daughters, taken away while loved ones, including children, stand by helplessly. In the aftermath, there usually are frantic calls to numbers that lead nowhere. It takes luck to reach an ICE officer who will answer any questions. The ICE Online Detainee Locator System—a public relations initiative ICE instituted following a series of wide-scale raids that resulted in mass “disappearances” —is hit or miss, more often a miss. If loved ones can get online—and most of the family members we encounter every day do not have access to the internet—they must either have the person’s “alien number” or the exact spelling of their name, date of birth and country of nationality. Then they must pass a “captcha” security check by typing in a word that appears in a box. Even lawyers have a difficult time getting the system to work. Despite having the necessary, accurate information, we still frequently get the message “detainee not found” if it is less than 24 hours since the arrest. It also takes the system a while to be updated following a transfer to a new detention center. This delay makes the first 24 hours or so following a person’s arrest all the more distressing for loved ones who realize a family member has gone missing.

Martin eventually reached his mother, after a collect call finally made it through to Viviana. He was later released from ICE custody after posting a bond. But months later, Viviana lives with the fear and guilt of those critical hours after Martin was taken away, when she believed her son to be missing and felt that she was responsible.

*Names have been changed to protect identity.

Claudia Valenzuela is the associate director of litigation for Heartland Alliance's National Immigrant Justice Center.