When I met Ahmed he had already spent six years in prison. My colleagues in NIJC’s LGBT Immigrant Rights Initiative and I knew that applying for protection under the Convention Against Torture was his only shot at avoiding deportation to Afghanistan, where he would likely be tortured or killed for being gay.

Ahmed was born in Afghanistan three years after the Soviet invasion. He grew up in the midst of civil war in a country where it is illegal to be gay and the penalty is death. Ahmed learned quickly that he had to keep his sexual orientation hidden. As a child, he confided in a friend at school about his feelings for other boys, but the friend told his parents and word spread quickly about Ahmed’s “condition.” The religious leaders of the village called a meeting with Ahmed’s father and demanded that he take his family and leave the village permanently. The only way that Ahmed’s father could convince them to allow his family to remain in the village was to promise them that he would do whatever it took to “change” Ahmed – presumably to make him heterosexual.

Ahmed was born in Afghanistan three years after the Soviet invasion. He grew up in the midst of civil war in a country where it is illegal to be gay and the penalty is death. Ahmed learned quickly that he had to keep his sexual orientation hidden. As a child, he confided in a friend at school about his feelings for other boys, but the friend told his parents and word spread quickly about Ahmed’s “condition.” The religious leaders of the village called a meeting with Ahmed’s father and demanded that he take his family and leave the village permanently. The only way that Ahmed’s father could convince them to allow his family to remain in the village was to promise them that he would do whatever it took to “change” Ahmed – presumably to make him heterosexual.

That night, Ahmed’s father beat him severely, leaving him with a broken nose and bad bruising. He and Ahmed’s mother admonished Ahmed for destroying the family name and threatened to kill him if he said another word to anyone about liking boys. Ahmed’s sexual orientation became a forbidden topic, but the family soon faced other problems.

Ahmed’s family supported the communist regime, which made them a target for the opposition insurgents. In 1995, the mujahedeen bombed Ahmed’s home, killing his mother and three siblings. Ahmed was forced to help clean up the wreckage after the bombing and remove the scattered limbs of his family members so that the remains could be properly buried. The following night, Ahmed’s father arranged for him and his sons to cross the border into Pakistan.

Ahmed spent eight tumultuous years coming of age as a gay man in Pakistan. He worked multiple jobs to support his father, who lived in a perpetual state of mourning after the death of Ahmed’s mother and siblings. Ahmed also suffered from his own post-traumatic stress that intensified over time, as he continued to suffer persecution because of his sexual orientation.

In Pakistan, Ahmed made friends with other gay men and transgender women. His friends warned him about the consequences of being open about his sexuality. Sure enough, Ahmed was arrested shortly after he began associating with them. Twice, the police arrested Ahmed and, after interrogating him about his sexual orientation, subjected him to brutal rape and physical beatings. Ahmed was raped by multiple officers during both of these arrests.

Ahmed and his father and brother finally entered the United States as refugees in 2003. They settled in Chicago, and Ahmed began working and received medications for depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) through refugee resettlement agencies. Ahmed struggled to cope with the painful memories of his family’s death and the sexual assaults he suffered in Pakistan. He attempted suicide shortly after his family arrived in the United States.

I spoke to Ahmed numerous times in the weeks leading up to his hearing, and we drafted his affidavit over the phone. He was usually in good spirits and was always very grateful for the time we put into preparing his case.

Michael Santos, who interned at NIJC this summer, represented Ahmed at his final merits hearing. Since an applicant’s criminal history is irrelevant for CAT purposes, we focused on the harm Ahmed suffered and would suffer if he returned to Afghanistan. The trial attorney brought the judge’s attention back to Ahmed’s criminal history every chance he could.

Ahmed had been convicted of attempted murder after his friend picked a fight with some men who had provoked them. His friend removed a baseball bat from his car, placed it in Ahmed’s hands and told him to swing. At the time of the incident, Ahmed had gone six months without receiving any of his mental health medications. His medical benefits had been cut off because he had not yet applied for permanent residence. In that moment, Ahmed reacted in a way that he normally would not if he had been receiving his medication, and afterward took full responsibility for his crime.

In the end, it was apparent to the judge that Ahmed was deeply troubled by the persecution and trauma he suffered, and that there was ample evidence that Ahmed would face severe torture or death as a gay man in Afghanistan. We received the decision in the mail, granting Ahmed deferral of removal under the Convention Against Torture and called him to relay the good news.

After I completed a final step of drafting and submitting a formal request for Ahmed’s release, he finally left the detention facility in August and is now in the care of his aunt and cousin in California. He is slowly adjusting to life outside of detention, and will soon be able to work legally in the United States.

I am grateful that I was able to help bring Ahmed’s story to the judge. It means a lot to me that someone who has been abused and assaulted his entire life can finally have a chance at a safe, open life in the United States.

Jackie Reidelberger is a Board of Immigration Appeals-accredited representative for NIJC's LGBT Immigrant Rights Initiative.

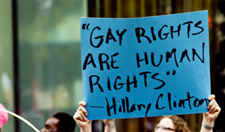

Photo credit: ep_jhu/Creative Commons