Striking the Balance: Emerging Legal Issues and Case Prioritization

By Lisa Koop

This conversation plays out frequently at immigration legal nonprofits serving immigrant children:

Attorney 1: We just completed intake with another child with a “future fear” forced recruitment gang case from El Salvador.

Attorney 2: Any past persecution?

Attorney 1: Not really. Gang members hung around his school. Some of his friends were forced to join. The gang approached him once but didn’t do anything after he said he needed time to think about joining.

Attorney 2: How many cases are on our pro bonocase list?

Attorney 1: 48. Two attorneys took cases last week and we have an asylum training next month. We can place a few cases there.

Attorney 2: Can we prepare this one in-house? Can an intern do it?

Attorney 1: We have eight in-house cases with approaching filing deadlines and have three Asylum Office interviews in the next month. It would be a stretch to add this case.

Attorney 2: Will he be able to hire someone if we decline?

Attorney 1: His family is at 87% of the poverty line, so probably not.

Attorney 2: Well, country condition documents suggest he will more than likely be recruited again if he’s returned. He’s already in removal proceedings, so he’s got nothing to lose.

Attorney 1: The particular social group would be Salvadoran males who resist gang membership? Or Salvadoran males who come from gang-controlled neighborhoods?

Attorney 2: We won’t win at the Asylum Office but he’s got a shot before the immigration judge and this is an issue we want to push…

Attorney 1: Yes, but we’ve already got a handful of similar cases in the works…

It pains children’s advocates to decline any colorable asylum case and a persistent voice tells them there is room for just one more case on the in-house docket. At the same time, advocates know that children’s asylum cases are almost always complex and difficult to prepare. The legal issues surrounding particular social group (PSG) asylum claims are complicated, nuanced, and ever-evolving. Child clients require more interviews of shorter duration to gather their stories. And the basic logistics of getting these clients to the office for meetings are often taxing. Advocates understand there is a point where trying to provide assistance in every case means something will fall through the cracks; a deadline will be missed, a client neglected, an argument made poorly. Given how high the stakes are in these matters, it is critical for advocates to be intentional about how they manage and sustain caseloads. Here are some best practices for managing case acceptance.

1. Keep the big picture in mind. Litigating one child’s case can impact subsequent cases for better or for worse. Though asylum officers and immigration judges do not issue precedential decisions, their future decisions are informed by their current caseload. Once cases have risen to the Board of Immigration Appeals and the federal courts of appeals, published decisions can alter the course of the law dramatically.

1. Keep the big picture in mind. Litigating one child’s case can impact subsequent cases for better or for worse. Though asylum officers and immigration judges do not issue precedential decisions, their future decisions are informed by their current caseload. Once cases have risen to the Board of Immigration Appeals and the federal courts of appeals, published decisions can alter the course of the law dramatically.

A. Make creative arguments. There is no set list of particular social groups from which advocates must choose when developing a case theory. Similarly, case law surrounding what constitutes a political opinion continues to evolve. The BIA has recognized that “married Guatemalan women in relationships they cannot leave” can be a PSG. Matter of A-R-C-G-, 26 I&N Dec. 388 (BIA 2014). Where gangs target children and select them as “girlfriends” against their wills, the same reasoning should apply. Several courts have recognized that individuals who are at risk of being trafficked can be a PSG. Cece v. Holder, 733 F.3d 662 (7th Cir. 2013). Likewise, children forced to do work for gangs are also victims of labor trafficking and may have asylum claims on that basis. If the bourgeoisie in some cultures can be a PSG, Benitez-Ramos v. Holder, 589 F.3d 426, 431 (7th Cir. 2009), and landowning class of cattle farmers qualify in others, Tapiero de Orejuela v. Gonzales, 423 F. 3d 666 (7th Cir. 2005), why not affluent Central Americans? Or individuals who have been Americanized? Cases involving “children without familial protection” and “female heads of household” are also gaining traction. And gender alone as a PSG remains potentially viable, Perdomo v. Holder, 611 F.3d 662 (9th Cir. 2010). Advocates should not accept that an argument that fails once will fail always. With different facts and/or before different adjudicators, the law is applied and interpreted differently. Advocates should not accept wholesale rejections of certain types of cases, but instead keep pushing the law to recognize the refugee status of children in need of protection.

B. Keep a finger on the legal pulse. Asylum case law changes often. Lawyers should refresh their knowledge regularly rather than merely recycle old briefings and arguments. While referencing current BIA and home circuit decisions may be most effective in briefing and before adjudicators, consider incorporating persuasive decisions from other circuits. Sign up to receive Board decisions as they are issued. The National Immigrant Justice Center blogs all circuit court immigration decisions. Creating and participating in listservs like those hosted by the National Immigration Project and working groups where practitioners share local practices – including the litigation practices of the ICE trial attorneys – can inform and improve litigation strategies.

C. Preserve issues. The law changes in ways that benefit children when advocates think strategically from the outset and contemplate BIA and federal court litigation. Issues only can be litigated on appeal when they have been preserved at the trial-court level. This means that advocates must make their records by briefing and arguing issues – even those that judges do not like and dismiss as nonstarters. For example, questions around the PSG analysis have been percolating in recent years. The NIJC’s practice advisory on PSG includes sample language advocates can use to preserve the ability to challenge the validity of the “social distinction” and “particularity” concepts, while also making arguments about eligibility under the Board’s current law.

D. Don’t concede that other arguments don’t work. There is little to be gained by conceding that a PSG cannot prevail. Some judges commonly make statements that gender alone never can be a PSG or that a PSG never can be defined by the harm an applicant has experienced. Neither of these statements is true – See Perdomo v. Holder, 611 F.3d 662 (9th Cir. 2010) and Lukwago v. Ashcroft,329 F.3d 157 (3d Cir. 2003) – and allowing the perception that they are settled legal issues undermines the larger advocacy effort. Take opportunities when they arise to educate adjudicators. Push back against unsupported assertions by ICE trial attorneys that threaten to mislead adjudicators. Understand case law in order to take a bold stand against any tide that threatens to undermine protection for children.

2. Think about who can really be helped. Implementing the above strategies is both time- and labor-intensive. Striving to win protection for one child while seeking to advance the aims of the overall movement is a significant undertaking. Advocates must make hard decisions about which cases to accept and which to decline. Having a protocol for case acceptance saves both time and anguish by establishing criteria for making these decisions. The following are suggested questions to ask when deciding which cases to accept:

A. Is this a winnable case? A very high percentage of children present colorable asylum claims and as discussed above, it behooves advocates to push the law to recognize them. But there are children who simply do not present asylum claims. Either they have no fear or the fear they express is entirely untethered from a protected ground or lacks evidentiary support. Advocates are hardwired to be sympathetic, but it is not responsible to advance a foundationless claim and see if it sticks. Clients are not well served by this strategy and advocates risk creating bad law for individuals who need asylum protection. Learn to say no to these cases.

B. Is this a child who can benefit from our representation? Some UICs present asylum claims but other obstacles prevent them from being clients who can be effectively served by a legal services organization. Does the child live within the organization’s geographic service area? Is she going to stay there? Can she arrange for transportation to the office for appointments? Does the child speak a language spoken by staff or for which an interpreter will be available? Is the child capable of cooperating with the lawyer or does she have behavioral issues that prevent her from participating in her representation? Where social services can be engaged to overcome these challenges, these obstacles need not be deal-breakers. But where these obstacles mean an advocate will be spending an inordinate amount of time on ancillary and logistical matters and prevented from providing effective representation, cases should be declined.

C. Is this child particularly vulnerable? Many legal services providers prioritize very young children, homeless children, mothering teens, and other subcategories of children. Identifying focus areas such as these can be a useful way to limit cases. However, remember that virtually no child is capable of navigating the complex immigration system alone and proceeding pro se is a terrible option for any asylum seeker.

D. Will this child find help elsewhere? Childrenwho have support systems to pay for private counsel should do so where competent private counsel is available. Likewise, legal services providers who can provide court representation to children may consider prioritizing court cases if other nonprofits in the community only provide representation before USCIS. Declining cases of potential clients who are most likely to find other counsel is a good strategy to preserve capacity for clients who have no other options.

E. Are we at capacity? While most legal service providers will be unable to identify a magic number at which the office reaches capacity, organizations should set a ballpark figure that can be used to guide case acceptance decisions. An attorney with limited other responsibilities probably has capacity to handle about 30 asylum cases per year. Where the attorney has strong paralegal support, that number may be higher. Where the attorney has other responsibilities, that number is likely to be lower. Though there will be variance across attorneys and organizations, developing and maintaining a case acceptance barometer is a good practice.

3. Suspend intake if necessary. Most legal services providers will reach capacity from time to time. When that happens, management must make the difficult decision to decline new cases. Failing to do so has the potential to put current clients at risk and also accelerates and exacerbates staff burnout, which can lead to attorney error and staff turnover. Staff likely will resist closing intake as they, too, will fear for the prospective clients unable to access help during the intake suspension. Organizations also will have to determine if closing intake is possible given obligations to funders and other stakeholders. However, closing intake may be the best among undesirable choices available to organizations that are operating at or beyond their capacity. The following are suggestions for managing an intake suspension.

A. Set temporal limits. It may be simplest to determine that closing intake for a set period of time will allow the organization the breathing room it needs to catch up on and resolve existing cases in order to create capacity for new matters. Most likely, a closure for less than a month will be insufficient. A three-month closure may strike the balance between shutting off the flow of new cases long enough to help staff manage their cases but not so long that potential clients and partners interpret the temporary closure as permanent.

B. Set trigger points. Another intake suspension model involves setting trigger points that, once reached, determine when intake is suspended and resumed. An organization may determine that when it has 50 cases awaiting pro bono placement, it has reached capacity and intake is suspended until the case number returns to 30. Having the upper and lower trigger points set this far apart means that intake will be suspended infrequently, but those suspensions may be somewhat lengthy since they will persist until the necessary number of cases is resolved.

C. Provide limited assistance. In conjunction with either of the models described above, organizations may consider providing limited support during intake suspension. For example, intake phone lines normally used to schedule intake appointments could remain open but be used to provide limited case support, guidance about things such as the one-year filing deadline, and referrals to other service providers. In the alternative, intake phone lines can be set to offer recorded messages that provide basic guidance, referrals, and links to web resources.

D. Consider pro se support. Most legalservices providers agree that pro se models are not well-suited for asylum matters and, in particular, are a poor fit for children. However, when legal services providers are unable to accept new matters and there are no other attorneys available, directing children and their custodians to pro se materials is an option that should be considered. The Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project has developed some of the best pro se materials available.

4. Take care of staff. The issue of staff burnout is raised here to address the ways organizations’ capacity issues impact staff and to offer practices intended to help make services for children sustainable.

A. Recognize the impact of intake on young staff. Seasoned practitioners may forget how harrowing it can be for staff new to this work to listen to story after story of persecution and abuse. Acknowledge to new staff members that intake can be difficult and invite them to raise concerns and/or to share if they are feeling overwhelmed. Some organizations place a cap on the number of intakes any individual may complete in a given week to create and support recovery time for intake workers.

B. Rotate staff on the front lines. Organizations should avoid having one individual handle all intake work. Involving other staff with intake will reduce the impact on any single individual and create a built-in support system for intake workers to share experiences with each other.

C. Address the challenges of intake with staff. Whether this happens at weekly case review meetings, designated staff retreats, or during the course of any given day, supervisors should be intentional about checking in with staff to ask about how they are handling intake. It may be appropriate to ask staff how they “decompress” or how they relax outside of work. Strongly encourage staff to take their vacation time and to use that time to disconnect from the work. Acknowledging that parts of the work can be emotionally difficult and prompting staff to think about ways they cope with the difficulties can help make the work more sustainable.

D. Give staff members resources to connect traumatized individuals with therapy. Feeling helpless in the face of the trauma of potential clients can be very taxing on intake workers. Once potential clients share their stories, staff often will feel compelled to offer support. Since legal intake workers are not therapists, help them know that their role is not to offer therapy, but rather to collect information that will help the legal team secure protection for potential clients, thus reducing the likelihood of new trauma. Simultaneously, many clients will need mental health care. Provide intake workers with referrals for mental health counselors who may be available to potential clients. Equip staff to explain to potential clients that while the role of legal workers is limited, they can help connect potential clients with specialists who can respond to their mental health needs. See Chapter 6 of this manual for more guidance in this area.

E. Direct staff to resources for themselves. Familiarize staff with counseling resources available to them. Organizations should have in-house options and help-lines available. Where that is not possible, ensuring that insurance policies offered through the organization cover psychological care is a good way to provide resources for staff members working on these difficult issues.

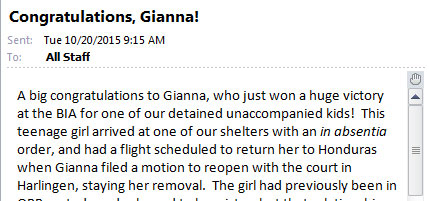

F. Celebrate victories. Few things make the work feel worthwhile more than seeing a child win her case. Be sure to celebrate the success of the child and those who made it possible. Supervisors might send an email to all staff members about successful cases or recognize them at staff meetings. Small gestures can have a big impact, like ringing a bell when a case is won or listing the case on an office chalkboard. Some offices celebrate court victories with ice cream or other treats. Take time to stop and appreciate the victories when they happen!

F. Celebrate victories. Few things make the work feel worthwhile more than seeing a child win her case. Be sure to celebrate the success of the child and those who made it possible. Supervisors might send an email to all staff members about successful cases or recognize them at staff meetings. Small gestures can have a big impact, like ringing a bell when a case is won or listing the case on an office chalkboard. Some offices celebrate court victories with ice cream or other treats. Take time to stop and appreciate the victories when they happen!