"When a person is sick, he needs help."

A mother whose son died by suicide in May following more than six years in immigration detention, together with an Illinois mother whose own mental health deteriorated rapidly during the 10 months she was locked up by immigration officials, called on members of Congress last week to end the U.S. government’s detention of immigrants. In a briefing with congressional staff, the women were joined by a neurologist doctor and a whistleblower who have worked for years to challenge U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) abuse of people with mental illness and use of solitary confinement.

The National Immigrant Justice Center (NIJC), which co-sponsored the briefing with Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas), filed a civil rights complaint in June demanding a system-wide investigation into ICE’s failures to provide adequate mental health care for people in its custody and its abusive use of solitary confinement.

Watch a recording of the virtual briefing

Participants in the briefing shared the following statements:

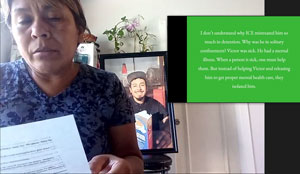

Rosa Lopez, is mother to Victor, who had schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, yet was detained for more than six years while his family and attorneys tried to prove he was a U.S. citizen. Victor died by suicide about five months after finally being released from detention.

with a portrait of Victor behind her.

“No entiendo por qué lo maltrataron tanto en la detención. ¿Por qué lo tenían solitario? Víctor estaba enfermo. Tenía una enfermedad mental. Cuando una persona está enferma, se debe ayudar. Pero en lugar de ayudar a Víctor y liberarlo para que recibiera atenciones médicas adecuadas, lo aislaron. Cuando un juez ordenó la liberación de Victor, fue un momento tan feliz, pero Victor estaba aterrorizado de que inmigracion lo enviara de regreso a la cárcel. Hice todo lo posible para conseguirle ayuda, pero fue difícil. Al final, todo fue demasiado para Víctor y se quitó la vida. No quiero que lo que le pasó a Víctor, le pase a otra persona. Víctor no pudo recuperarse cuando salió por todo el daño que sufrió por estar detenido tanto tiempo. Por no recibir el tratamiento que necesitaba. Por estar completamente solo.”

“I don't understand why they mistreated him so much in detention. Why did they keep him in solitary? Victor was sick. He had a mental illness. When a person is sick, he needs help. But instead of helping Victor and releasing him to receive proper medical attention, they isolated him. When a judge ordered Victor's release, it was such a happy moment, but he was terrified that immigration would send him back to jail. I did my best to get him help, but it was difficult. In the end, it was all too much for Victor and he took his own life. I don't want what happened to Victor to happen to someone else. Victor couldn't recover when he got out because of all the damage he suffered from being detained for so long. For not receiving the treatment he needed. For being all alone.”

Angela Osorio, an Illinois mother, was formerly detained in two ICE jails for 10 months, where she suffered a rapid decline in her mental health.

“ICE released me from detention and my depression came with me. I try to take medication for my depression, but it’s like I never really left detention. My children are the only thing that gives me the strength to keep going. I don’t want anybody to go through what I went through. … I want the chapter to end, but people need to know what happens. I want you to know my story for the people who are still inside suffering.”

Nubia Fimbres, NIJC policy associate, was author of the civil rights complaint.

“In speaking with people for the civil rights complaint we filed and especially in speaking with Angela, one of our panelists, I was reminded that detention itself is disabling. Whether or not someone enters detention already experiencing mental illness and disability, the chances that they will leave with lasting mental health challenges are high.”

Dr. Altaf Saadi, general neurologist and hospital neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, authored a declaration in support of NIJC’s civil rights complaint based on her experience providing medical and psychological evaluations for dozens of individuals in ICE detention.

“Among detention staff, there is a widespread assumption that medical concerns of detained individuals are not legitimate, and that they are exaggerating symptoms. There is a lack of basic respect for those seeking treatment, which runs contrary to how a therapeutic relationship with any individual should be developed.”

Ellen Gallagher, Department of Homeland Security whistleblower represented by Government Accountability Project, raised internal alarms in 2014 about ICE’s use of solitary confinement on medically vulnerable and mentally ill people, and exposed the abusive practices publicly in 2019.

“Over and over I found information confirming that seriously mentally ill and other medically vulnerable detainees were being placed into solitary confinement for reasons directly related to — or caused by — their illness; they were deprived proper medical care and attention, even when suicidal; and, missed immigration court dates that otherwise might have enabled them to seek bond, legal protection or relief, and counsel. Subjecting seriously mentally ill and medically vulnerable detainees to solitary confinement clearly violates ICE detention standards and ICE’s segregation directive, not to mention disability law and due process.”